Fibromyalgia is an incredibly complex, widespread, and disabling neuromusculoskeletal disorder. Fibromyalgia affects between 2-8% of the American population, somewhere between 6 million to 25 million individuals (1). A literature search of the National Library of Medicine of the United States using the key work “fibromyalgia” will locate 8,489 citations (May 8, 2015).

Daniel Clauw, MD, is a Professor of Anesthesiology, Medicine (Rheumatology) and Psychiatry at the University of Michigan. In May, 2015, Dr. Clauw published a study in the journal Mayo Clinical Proceedings, titled (2):

Fibromyalgia and Related Conditions

The abstract from this publication includes these points:

“Fibromyalgia is the currently preferred term for widespread musculoskeletal pain, typically accompanied by other symptoms such as fatigue, memory problems, and sleep and mood disturbances, for which no alternative cause can be identified.”

“Earlier there was some doubt about whether there was an ‘organic basis’ for these related conditions, but today there is irrefutable evidence from brain imaging and other techniques that this condition has strong biological underpinnings, even though psychological, social, and behavioral factors clearly play prominent roles in some patients.”

“The pathophysiological hallmark is a sensitized or hyperactive central nervous system that leads to an increased volume control or gain on pain and sensory processing. This condition can occur in isolation, but more often it co-occurs with other conditions now being shown to have a similar underlying pathophysiology (eg, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and tension headache) or as a comorbidity in individuals with diseases characterized by ongoing peripheral damage or inflammation (eg, autoimmune disorders and osteoarthritis).”

“The term centralized pain connotes the fact that in addition to the pain that might be caused by peripheral factors, there is superimposed pain augmentation occurring in the central nervous system.”

“It is important to recognize this phenomenon (regardless of what term is used to describe it) because individuals with centralized pain do not respond nearly as well to treatments that work well for peripheral pain and preferentially respond to centrally acting analgesics and nonpharmacological therapies.”

It is the “nonpharmacological therapies” that are emphasized in this review.

The world’s leading authority on fibromyalgia is Fredrick Wolfe, MD. Dr. Wolfe is a Clinical Professor of Medicine at the University of Kansas School of Medicine. A search of the National Library of Medicine of the United States using the key words “wolfe f AND fibromyalgia” finds 119 articles.

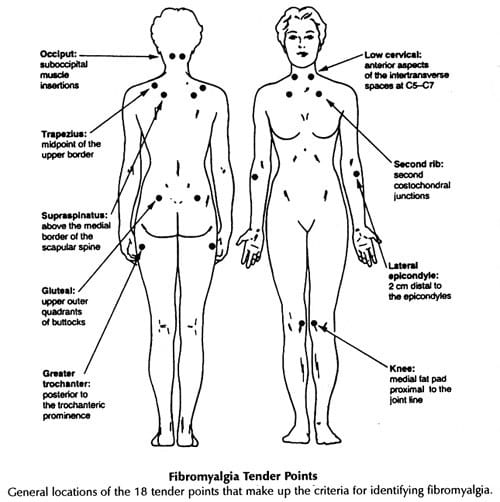

In 1990, Dr. Wolfe and colleagues published the Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia for the American College of Rheumatology (3). To complete this task, Dr. Wolfe and colleagues studied 558 consecutive patients: 293 patients with fibromyalgia and 265 control patients. Trained, blinded assessors performed interviews and examinations. The authors concluded that the clinical diagnosis of fibromyalgia required both of the following:

- Widespread pain (axial plus upper and lower segment plus left and right-sided pain).

- Excessive tenderness at 11 or more of 18 specific tender point sites.

These fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria became the standard for the next 20 years, from 1990 to 2010. The location of the 18 specific tender point sites is included below:

In 2010, Dr. Wolfe and colleagues updated the Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia for the American College of Rheumatology (4). There had been a growing concern in the original diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia that relied significantly on the presence of tender points. This is because of the fact that women in general are more sensitive to pressure point tenderness than are men. Relying on pressure point tenderness could cause a sex bias, which might account for the finding that about 90% of diagnosed fibromyalgia sufferers are women. It had become apparent that the “focus on tender points was not justified.” (5) Consequently, Dr. Wolfe and colleagues developed simple, practical criteria for clinical diagnosis of fibromyalgia that did not require a tender point examination, and to provide a severity scale for characteristic fibromyalgia symptoms (4). Specifically, they used an amalgamation of two prior developed assessment protocols:

1) The Widespread Pain Index (WPI)

This is a measure of the number of painful body regions (a total of 19 locations).

2) The Symptom Severity (SS) Scale.

This scale is designed to grade adjunct fibromyalgia symptoms, specifically cognitive symptoms (trouble remembering or thinking), un-refreshed sleep, fatigue, and number of somatic symptoms.

A sample of the questionnaire is included below.

The authors concluded that this simple form correctly classified 88.1% of fibromyalgia cases, and that classifying fibromyalgia “does not require a physical or tender point examination.” This approach to the diagnosis of Fibromyalgia Syndrome continues to be supported (6). To diagnose fibromyalgia, patients should:

- Have pain in a number of areas of the body, widespread pain (upper body, lower body, left side, right side).

- Be substantially bothered by fatigue.

- Have difficulty in getting restful sleep.

- Often have problems with memory or thinking clearly.

New Fibromyalgia Diagnostics 2010

All Three Are Needed For the Diagnosis of Fibromyalgia Syndrome

1) Either WPI ≥ 7 and SS ≥ 5 OR WPI 3 – 6 and SS ≥ 9

2) Symptoms are present and essentially unchanged for ≥ 3 months

3) There is no alternative explanation for the pain

Widespread Pain Index | Score: 1 For Each Spot |

| Shoulder Girdle L | |

| Shoulder Girdle R | |

| Upper Arm L | |

| Upper Arm R | |

| Lower Arm L | |

| Lower Arm R | |

| Hip (buttock/trochanter) L | |

| Hip (buttock/trochanter) R | |

| Upper Leg R | |

| Upper Leg L | |

| Lower Leg L | |

| Lower Leg R | |

| Jaw L | |

| Jaw R | |

| Chest | |

| Abdomen | |

| Upper Back | |

| Lower Back | |

| Neck | |

| Total WPI (0-19) |

| Symptom Severity (SS) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Fatigue | No Problem | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Waking up Un-refreshed | No Problem | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Cognitive Symptoms(trouble remembering or thinking) | No Problem | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Number of Somatic Symptoms | None | Few | Moderate | Many |

Total Symptom Severity (SS): (0-12)

Recent studies have assessed the influence of spinal mobilization and/or manipulation on the clinical status of patients with fibromyalgia.

In 2014, Michel Reis and colleagues from the School of Medicine, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, published a study in the journal

Rehabilitation Research and Practice titled (7):

Effects of Posteroanterior Thoracic Mobilization on Heart Rate Variability and Pain in Women with Fibromyalgia

These authors note that fibromyalgia is classically characterized by chronic pain, fatigue, depression, insomnia, and reduced cognitive performance. In addition, fibromyalgia is also associated with cardiac autonomic abnormalities.

Heart rate variability is used to investigate cardiovascular autonomic abnormalities. It is a simple, sensitive, and noninvasive tool. Heart rate variability is reduced in fibromyalgia with increased sympathetic tone and activity. It is thought that there is a relationship between increased sustained sympathetic activity and tone and the symptoms of fibromyalgia. Studies suggest autonomic imbalance mechanistically contributes to the symptoms of fibromyalgia. The autonomic imbalance for fibromyalgia is characterized by sympathetic hyperactivity at rest.

Sympathetic hyperactivity may also be responsible for frequent complaints of cold extremities in fibromyalgia patients. Studies have shown that fibromyalgia may be related to changes in autonomic tone, shifting toward an increase in sympathetic activity.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of one session of a posteroanterior (P-A) glide technique on both autonomic modulation and pain in woman with fibromyalgia. The study used 20 women, half with diagnosed fibromyalgia. This is the first study to demonstrate the effect of a posteroanterior glide mobilization to the thoracic spine on autonomic modulation in patients with fibromyalgia. The mobilization technique used in this study was passive P-A push, sustained for 60 seconds at the T1-T2 spinal level, “corresponding to the thoracic sympathetic preganglionic neurons.”

The upper thoracic mobilization was able to improve heart rate variability and improve autonomic profile through increased vagal activity. In women with fibromyalgia and impaired cardiac autonomic modulation, one session of spinal mobilization was able to acutely improve heart rate variability. In addition, the authors note that, in agreement with other studies, manual therapy protocols are effective in improving pain intensity in fibromyalgia patients. Their conclusions include:

This study shows that “patients with fibromyalgia have increased sympathetic activity and decreased activity in the vagal control of heart rate.” “This sympathetic excitation could contribute to the diffuse pain and tenderness at specific points experienced by patients with fibromyalgia.”

“The potentially significant impact of our findings is the demonstration that only one session of this manual intervention to the thoracic spine was able to modify heart rate variability in women with fibromyalgia.”

“It is plausible to hypothesize that the posteroanterior glide technique utilized in the current study may significantly contribute to reducing the debilitating signs and symptoms of fibromyalgia, improve quality of life, and reduce cardiovascular risk when applied for more than one session.”

There is an optimum balance of activity between the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems. When the balance is disrupted, it adversely influences the entire body, including pain thresholds. Dysfunctional spinal joints increase sympathetic tone, creating an imbalance with parasympathetic tone. Applied mechanical forces (manual therapy, mobilization/manipulation) to the dysfunctional spinal joints inhibits sympathetic tone, restoring autonomic balance, improving homeostasis and reducing pain thresholds.

••••

David Vallez Garcia (from The Department of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands) and colleagues contributed a chapter in a 2014 book titled PET and SPECT in Neurology, pertaining to the physiology of chronic pain (8). In their review, the authors note:

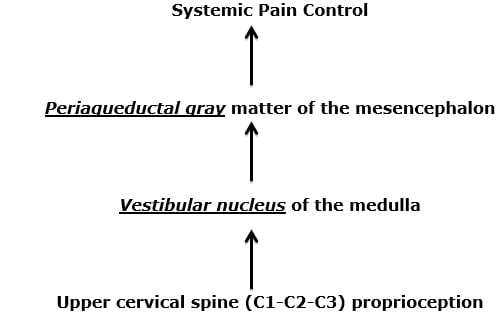

- Pain, anywhere in the body, is controlled by the periaqueductal gray (PAG) matter of the mesencephalon (the midbrain, at the top of the brainstem).

- A major contributor to the periaqueductal gray matter is the vestibular nucleus (VN) of the medulla (the bottom of the brainstem).

- The vestibular nucleus is also critically involved in posture control.

- A major contributor to the vestibular nucleus is the proprioceptive neurology from the upper cervical spine, specifically from C1-C2-C3. This proprioception arises form neck muscle spindles, ligaments, and joint capsules.

Consequently, these authors propose this mechanism for widespread somatic pain syndromes: Mechanical dysfunction of the joints of the upper cervical spine alters the quality of the proprioceptive input from the upper cervical spine muscles, ligaments, and capsules to the vestibular nucleus. The vestibular nucleus becomes less efficient in activating the pain control neurons of the periaqueductal gray matter, resulting in increased chronic widespread body pain syndromes.

These authors note:

“More than 30% of all the spinal-periaqueductal gray fibers originate from the C1-C3 spinal segments.”

Chronic pain symptoms are the “result of a mismatch between aberrant information from the cervical spinal cord and the information from the vestibular and visual systems, all of which are integrated in the mesencephalic periaqueductal gray and adjoining regions.”

Chronic pain symptoms are due to a “mismatch in the midbrain and other structures via the upper cervical cord to the mesencephalon on the one hand and the intact information from the vestibular and visual systems to the mesencephalon on the other hand.”

This chapter supports the perspective that chronic pain syndromes occur as a consequence of poor quality proprioceptive (mechanoreception) input from soft tissues into the central neural axis, and that management should be directed towards improving mechanical function of the dysfunctional soft tissues. This very much supports the chiropractic approach to management of chronic pain patients, especially chiropractic care that targets the function of the joints of the upper cervical spine.

Are there any studies evaluating manipulation of the upper cervical spine in the treatment of patients suffering from fibromyalgia? See below:

•••••

In March 2015, Drs. Ibrahim M. Moustafa and Aliaa A. Diab, from the Basic Science Department, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt, published a study in the journal Rheumatology International, titled (9):

The addition of upper cervical manipulative therapy in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial

The aim of this study was to investigate the immediate and long-term effects of a one-year multimodal program, with the addition of upper cervical manipulative therapy, on fibromyalgia management outcomes in addition to three-dimensional (3D) postural measures. It is a prospective, randomized, clinical trial.

These authors note that fibromyalgia syndrome is a common and chronic disorder manifested by increased pain sensitivity and a number of other symptoms such as fatigue, stiffness, non-restorative sleep patterns, memory and cognitive difficulties, and reduced quality of life. Long-term treatment outcomes on fibromyalgia patients “are typically poor.” A survey of 1200 primary care physicians in the USA found that only 14% of respondents indicated very good or excellent satisfaction with the management of patients with fibromyalgia (10).

Published theories as to the cause of fibromyalgia include:

- Poor nutrition

- Stress

- Alterations in sleep patterns

- Changes in neuroendocrine transmitters

- Poor posture

- Cervical spine dysfunction

- Abnormal afferent processing and/or abnormal sensorimotor integration

This is a randomized clinical trial with a one-year follow-up, assessing 120 patients with fibromyalgia syndrome and definite C1-2 joint dysfunction. Subjects were assessed at 12 weeks (at the end of the treatment program) and again at a 1-year follow-up period. The subjects were randomly assigned to the experimental [upper cervical manipulation] group (n = 60) or the control group (n = 60). Both groups completed a 12-week multimodal program consisting of an education program, cognitive behavior therapy, and an exercise program.

The education program consisted of one 2-hour session per week for 12 weeks, and included:

- Information about typical symptoms

- The usual course for fibromyalgia

- Potential causes of fibromyalgia

- The influence of psychosocial factors on pain

- Current pharmacologic and non-pharmacological treatments for fibromyalgia

- The benefits of regular exercise on fibromyalgia

The cognitive behavior therapy consisted of one 2-hour session per week for 12 weeks, and included educational, physical, cognitive, and behavioral elements.

The exercise program was conducted for 1 hour three times per week for 12 weeks. The participants were instructed to perform the relaxation exercises at home twice daily as their home routine.

The upper cervical spinal manipulation group consisted of both:

- Low-velocity cervical joint mobilization techniques

- High-velocity manipulation techniques for the treatment of cervical joint disorders

- Upper cervical manipulative therapy was conducted in 12 treatments (three times per week) over a one-month period in addition to maintenance spinal manipulations in one session per week for the following 8 weeks. [3X/week for 4 weeks, then 1X/week for 8 weeks]

The group receiving upper cervical spinal manipulation showed significant improvements in spinal posture. After 12 weeks of treatment, the two treatment arms were roughly equally successful in improving the fibromyalgia management outcomes. However, at the 1-year follow-up, the upper cervical spinal manipulation group showed greater improvements in all the fibromyalgia measurement outcomes. These authors made the following points:

“Increasing evidence suggests that spinal dysfunction, particularly in the upper cervical region (which has more mechanoreceptors per unit surface area than any other region of the spinal column), might affect central neural processing and potentially lead to maladaptive central plastic changes.”

“Cervical manipulation might help to modulate disordered sensorimotor integration and thus counteract changes in the processing of sensory information in the brain and spinal cord.”

“Upper cervical manipulation might be required to achieve optimal full-spine postural correction because the rest of the spine orients itself in a top-down fashion.”

“At the one-year follow-up after the end of the treatment, there were statistically significant changes that indicated that the fibromyalgia syndrome management outcomes of the experimental [upper cervical manipulation] group exhibited continued improvement and that the control subjects’ scores regressed back toward the baseline values (i.e., the scores worsened).”

“The one-year improvements in the FMS management outcome measures observed in the experimental [upper cervical manipulation] group are the most significant findings of our investigation.”

“Sustained postural imbalances can result in the establishment of a state of continuous asymmetric loading. Once this state is established and maintained beyond critical weight and time threshold, degenerative changes in the muscles, ligaments, bony structures, and neural elements increase.” When postural asymmetry is reversed, and the unbalanced loading is thereby corrected the “reversible of these degenerative changes or even their improvement requires some time.”

“The continuous asymmetrical loading and muscle imbalance that results from biomechanical dysfunction due to abnormal spinal posture in the sagittal, transverse, and coronal planes elicits abnormal stress and strain in many structures, including the bones, intervertebral disks, facet joints, musculotendinous tissues, and neural elements and causes a barrage of nociceptive afferent input that results in dysafferentation.”

“Importantly, our results from the one-year follow-up revealed statistically significant changes that favored the experimental [upper cervical manipulation] group’s outcomes in terms of all of the fibromyalgis management outcome variables.”

“The addition of the upper cervical manipulative therapy to a multimodal program is beneficial in treating patients with fibromyalgia syndrome.”

This is an important study, and the data suggests this model:

Fibromyalgia is a multifaceted problem that tends to be linked to poor posture. This is because the postural system controls a large quantity of the afferent neurology into the central neural axis.

The upper cervical spine has more afferent neurons that enter the central neural axis than any other spinal region. In addition, upper cervical afferents communicate mono-synaptically in the vestibular nucleus.

The vestibular nucleus controls whole body posture.

Upper cervical spinal manipulation makes a significant and lasting improvement on whole body posture by influencing the vestibular nucleus.

This study also indicates that the benefits of chiropractic postural corrections take time to manifest, but once these benefits are obtained, they tend to be long lasting.

These authors imply that new guidelines for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome should be established and they should include upper cervical manipulation.

SUMMARY

Six to 25 million Americans suffer from fibromyalgia syndrome. Their symptoms are chronic, treatment resistant, and often debilitating. Only 14% of traditionally managed fibromyalgia patients achieve an acceptable clinical outcome.

Components of the proposed pathophysiology of fibromyalgia suggest that chiropractic mechanical care, especially of the upper cervical spine, makes biologically plausible sense. The evidence suggests that chiropractic care, along with other traditional approaches, result in significant clinical improvement for these patients, and that the improvement is long lasting. All chronic fibromyalgia patients should engage in chiropractic segmental and postural spinal corrections.

REFERENCES

- Clauw DJ; Fibromyalgia: a clinical review; Journal of the American Medical Association; April 16, 2014; 311(15):1547-55.

- Clauw DJ; Fibromyalgia and Related Conditions; Mayo Clin Proc; May 2015;90(5):680-692.

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, Tugwell P, Campbell SM, Abeles M, Clark P et al.; The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee; Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Feb;33(2):160-72.

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P, Russell AS, Russell IJ, Winfield JB, Yunus MB; The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity; Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken); 2010 May;62(5):600-10.

- Smith HS, Harris R, Clauw DJ; Fibromyalgia: An Afferent Processing Disorder Leading to a Complex Pain Generalized Syndrome; Pain Physician; 2011; 14:E217-E245.

- Häuser W, Wolfe F; Diagnosis and diagnostic tests for fibromyalgia (syndrome); Reumatismo; Sep 28, 2012;64(4):194-205.

- Reis MS, Durigan JL, Arena R, Rossi BR, Mendes RG, Borghi-Silva A; Effects of Posteroanterior Thoracic Mobilization on Heart Rate Variability and Pain in Women with Fibromyalgia; Rehabilitation Research and Practice; May 29, 2014 [epub].

- Garcia DV, Dierckx R, Otte a, Holstege G; PET and SPECT in Neurology, Chapter 46 “Whiplash: Real or Not Real: A Review and New Concept”; Springer-Verlag; 2014, pp. 947-963.

- Moustafa IM, Diab AA; The addition of upper cervical manipulative therapy in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial; Rheumatology International; March 18, 2015 [epub].

- Hartz AJ, Noyes R, Bentler SE et al; (2000) Unexplained symptoms in primary care: perspectives of doctors and patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 22:144–152.