One of the best reference books pertaining to the spine is appropriately titled:

The Spine

The editors of The Spine are Richard Rothman, MD, PhD, and Frederick Simeone, MD. When the second edition of their book was published in 1982, Dr. Rothman was a Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery, The University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, and Chief of Orthopedic Surgery at the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. A recent internet search reveals that Dr. Rothman remains in clinical practice, has published 13 textbooks and over 200 original research papers, and serves as the Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Arthroplasty.

In 1982, Dr. Frederick Simeone was Professor of Neurosurgery, The University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; Chief of Neurosurgery at the Pennsylvania Hospital; and Director of Neurosurgery at the Elliott Neurological Center of Pennsylvania Hospital. Dr. Simeone also remains in clinical practice.

The Spine, edited by Rothman and Simeone, also includes 30 distinguished contributing authors. Chapter 2 of the book is titled:

“Applied Anatomy of the Spine”

This chapter is written by Wesley Parke, PhD. In 1982, Dr. Parke was Professor and Chairman, Department of Anatomy, University of South Dakota School of Medicine. In this chapter, Dr. Parke writes:

“Although the 23 or 24 individual motor segments must be considered in relation to spinal column as a whole, no congenital or acquired disorder of a single major component of a unit can exist without affecting first the functions of the other components of the same unit and then the functions of other levels of the spine.”

I believe that the point of Dr. Parke’s comments is that although spinal biomechanical function and pathology is often discussed in terms of the segmental motor unit and all of its components, that in fact the entire spinal column is an integrated functioning unit. Specifically, this would indicate that a cervical spine disorder could influence the function and symptomatology of the lower back, and visa versa.

The concept of the entire spine acting as a single integrated functioning entity is further supported by the reference text written by rheumatologist John Bland, MD, in his 1987 text:

Disorders of the Cervical Spine

Dr. Bland is a Professor of Medicine at the University of Vermont College of Medicine. Dr. Bland writes:

“We tend to divide the examination of the spine into regions: cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine clinical studies.

This is a mistake.

The three units are closely interrelated structurally and functionally – a whole person with a whole spine.

The cervical spine may be symptomatic because of a thoracic or lumbar spine abnormality, and vice versa!

Sometimes treating a lumbar spine will relieve a cervical spine syndrome, or proper management of cervical spine will relieve low backache.”

Over the decades, a number of publications indicate that cervical spine problems can influence the biomechanics, the perception of pain and the neurology of the low back. All of the afferent neurology from the low back and lower extremities must pass through the cervical spinal cord on its way to the brain. All of the motor controls from the brain must travel through the cervical spinal cord on its way to the low back and lower extremities. Mechanical problems of the cervical spine may interfere with the normal transmission of this afferent and efferent neurological transmission.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1942, resulted in unbelievable injuries to American soldiers and civilians. The only neurosurgeon in the Hawaiian Islands was a young Army Lieutenant named Ralph B Cloward (1908-2000). Dr. Cloward operated on the wounded for 4 straight days without sleep, saving countless lives. For the next 5 weeks, Dr. Cloward traveled from hospital to hospital, performing life-saving surgeries from early morning to late at night. Throughout his career, Dr. Cloward pioneered numerous diagnostic and spinal surgical techniques.

In December 1959, Dr. Cloward published in the journal Annals of Surgery an article titled:

Cervical Diskography

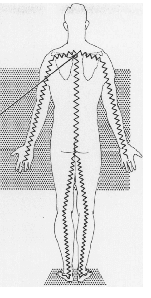

In this article, Dr. Cloward clearly notes that spinal cord compression by a midline cervical disc protrusion can cause pain extending down to the feet (see picture). He writes that a “small midline protrusion [of a cervical disc] often causes no pain or mild discomfort in the back of the neck.” Yet irritation of the long sensory pathways of the spinal cord, as originally described by L’Hermitte, can illicit pain in the coccyx or down the spine, into the lower extremities, and to the toes.

In 1964, physician FW Gorham published an article in the journal California Medicine titled:

Cervical Disc Injury

Symptoms and Conservative Treatment

Dr. Gorham writes:

“Primary traumatic cervical disc disease and chronic disc disease associated with spondylitis aggravated by injury causes referred pain to the head, face, neck, arms, shoulders and chest, and even in the lower back.

Such pain may be reproduced by the injection of contrast medium for cervical discography.”

“Backache and coccygeal pain occur and may be related to dural irritation.”

Although Dr. Gorham’s paper is well referenced, he infuses significant observations from his clinical practice in Santa Ana, California.

In May of 1967, physicians Thomas Langfitt and Frank Elliott published an article in the Journal of The American Medical Association, titled:

Pain in the Back and Legs Caused by Cervical Spinal Cord Compression

Drs. Langfitt and Elliott were from the Department of Neurosurgery at the Pennsylvania Hospital and from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Their article is both a literature review and the presentation of three demonstrative case studies. These authors write:

“Cervical spinal cord compression by tumor or degenerated disk material can cause low back and leg pains which simulate the lumbar disk syndrome.”

“The pain caused by [cervical] cord compression tends to be diffuse, involves both legs, and is burning or aching in quality.”

“The results of neurologic examination may be normal at a time when [cervical] cord compression is sufficient to produce severe pain.”

“The mechanical signs of lumbar disk herniation, limitation in back mobility, and a positive reaction to the straight leg raising test are absent with [cervical] cord compression.”

“The most common causes of spinal cord compression are degeneration of intervertebral disks with herniation of the nucleus pulposus into the spinal canal or the formation of osteofibrous ridges at the junction of the disk and the vertebral body. This later conditions is termed spondylosis.”

“The earliest symptoms [of cervical spinal cord compression secondary to spondylosis] may be sensory, in the form of numbness or paresthesia of the legs, or weakness of the legs due to involvement of the corticospinal tracts.”

Importantly, these author note that the lower extremity symptoms can be unilateral or bilateral, that the patients often have no neurological signs of spinal cord involvement, and there may be no cervical or upper extremity symptoms.

In October 1973, physicians Herbert Lourie and colleagues publish an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, titled:

The Syndrome of Central Cervical Soft Disk Herniation

Dr. Lourie and colleagues are from the Department of Neurosurgery, State University of New York, Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse, New York. In this article, these physicians present six case studies. These authors note that in cervical myelopathy:

“The common initial complaints are those of an unsteady gait and of a subjective feeling of numbness in the trunk and lower extremities.”

“There may be some variability of the clinical picture, but spasticity with or without weakness in the lower extremities is a uniform feature.”

In support of the clinical observations noted above is the 1980 book by Herman Kabat, MD, PhD, titled:

Low Back and Leg Pain From Herniated Cervical Disc

Dr. Kabat is a specialist in physical medicine. In 1946, with the industrialist Henry J. Kaiser (1882-1967), he established the Kabat-Kaiser Institute in Vallejo, California. One of the purposes of the institute was to conduct medical research in neuromuscular disorders. Although Dr. Kabat was born in 1913, a current internet search suggests he is still living. Dr. Kabat writes:

“Herniated cervical disc has been shown to be caused by trauma.

This disorder is much more common than was previously recognized and can occur at almost any age, even in childhood.

This investigation has demonstrated conclusively that compression of the cervical spinal cord by the herniated nucleus pulposus of the cervical disc is the most common cause of low back and leg pain.

Conservative treatment exclusively of the herniated cervical disc in a large series of cases has routinely produced complete and lasting relief of pain in the low back and leg.

The low back and leg pain and associated complaints from compression of the cervical spinal cord by the herniated nucleus pulposus of the cervical disc are usually indistinguishable from the characteristic symptoms of a herniated lumbar disc.

In many cases, pain in the low back and leg is the only complaint from herniation of the cervical disc, without pain in the neck or arm that would call attention to a disorder of the cervical spine.

In a large series of cases previously attributed to a variety of disorders in the lumbosacral region, the low back and leg pain was shown to be entirely associated to the herniated cervical disc.

In patients for whom immediate lumbar laminectomy was recommended elsewhere for herniated lumbar disc confirmed by recent lumbar myelography, the pain in the low back and leg proved to be the result solely of herniated cervical disc.

Furthermore, patients who had failed to obtain relief from lumbar disc surgery were found to have a herniated cervical disc which was exclusively responsible for the low back and leg pain.

Pain in the low back and leg without neurological findings has been reported from compression of the cervical spinal cord by tumors, cervical spondylosis and a herniated nucleus pulposus of a cervical disc.

Although it is well established that compression of the cervical spinal cord can cause low back and leg pain, this has not been generally known and it has been largely ignored in management of patients with this complaint.”

Dr. Kabat attributes the low back and leg symptoms caused by herniation of a cervical disc to impingement upon the long tracts of the cervical spinal cord. He indicates that the low back and leg symptoms include pain, paresthesia, hypoesthesia, paresis and scoliosis. Dr. Kabat stresses that the primary complaint is pain to the lower back and leg, while noting that any combination can occur: low back and leg pain; low back pain alone, or leg pain alone. The leg pain may be unilateral or bilateral, and on occasion it will alternate. He notes that the pain may be constant or intermittent. Most importantly, Dr. Kabat writes:

Because the compression of the cervical spinal cord is by a protruded soft disc, these complaints, even if intense or of long duration, are completely reversible by conservative treatment exclusively of the herniated [cervical] disc, except for the rare manifestation of myelopathy.”

Perhaps, the best explanation for a cervical disc herniation causing low back and leg symptoms without producing symptoms in the upper extremities can be found in reference text Gray’s Anatomy. Gray’s Anatomy shows an axial view picture of the spinal cord showing its somatotopic organization (below, Gray’s Anatomy, 39th edition, 2005, p. 318). In oversimplification, the spinal cord appears like a bull’s eye target. The outer rings of the target (spinal cord) are the motor and sensory innervation to the perineum, legs and low back; while inner rings of the target (spinal cord) are the motor and sensory innervation to the upper extremities.

Central canal spinal stenosis of the cervical spine (subsequent to disc herniation, spondylosis, etc.) is essentially an irritation to the spinal cord from the outside towards the center. Consequently, central canal spinal stenosis primarily adversely affects the outer rings of the target (spinal cord), thereby affecting the nerve fibers that innervate the perineum, legs and low back. This would adequately explain the presence of more low back and leg symptoms that upper extremity symptoms.

Consistent with these studies and anatomical descriptions, in 1996, physician Shinichi Kikuchi and colleagues published an article in the journal Spine, titled:

Spinal Intermittent Claudication Due to Cervical and Thoracic Degenerative Spine Disease

Dr. Kikuchi and colleagues are from the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Fukushima Medical Center in Fukushima, Japan, and the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Japan Red Cross Medical Center in Tokyo,Japan. In their study pertaining to cervical and/or thoracic central canal stenosis subsequent to spondylosis and resulting in spinal cord compression, the primary documented impairment was “walking intolerance.”

Most recently, and once again consistent with these studies and anatomical descriptions, in January 2009, physician Yasutsugu Yukawa and colleagues published in the journal Spine titled:

“Ten Second Step Test" as a New Quantifiable Parameter of Cervical Myelopathy

Dr. Yukawa and colleagues are from the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Chubu Rosai Hospital in Nagoya, Japan. In their article they designed a clinical and cohort study to test the clinical effectiveness of a quantifiable measure of severity in cervical compressive myelopathy, which they termed the “Ten-Second Step Test.” Their study included 163 preoperative patients with cervical compressive myelopathy and 1,200 healthy volunteers. The study population included 99 men and 64 women with a mean age of 63.3 years (range, 33-92). Importantly, these authors are assessing the severity, prognosis and clinical outcomes of patients suffering from cervical compressive myelopathy by counting the number of lower extremity steps they could perform in a ten-second period of time. These authors write:

“Cervical compressive myelopathy is one of the most common neurologic disorders increasing in the geriatric population. It is caused by cervical spondylosis, disc herniation, and ossification of the longitudinal ligament. Symptoms include sensory disturbances of the extremities, clumsiness of hands, gait disturbance, and urinary dysfunction.”

“Patients with myelopathy experience difficulty in taking a step while walking, due to disorders of position sense and locomotor disability in the lower extremities, which reflect long tract pathology.”

“Hence, it was assumed that the step test could be used as a scale to quantify the severity of cervical compressive myelopathy.”

In this study, the patients and controls “were instructed to take a step by lifting their thighs parallel to the floor (hip and knee joints in 90° flexion) in the same place without holding onto any object for balance. The number of steps in 10 seconds was counted. Each patient and control was requested to perform the test at maximum speed.” These authors conclude:

“A new locomotor scale 10 second step test was investigated to determine if it could be used as a quantifiable parameter for cervical compressive myelopathy.

The present study demonstrates that the step test can reflect and quantify the severity of cervical compressive myelopathy.

This test can easily be performed anywhere and at any time without the requirement of a special instrument and repeated if necessary, as it is sensitive to neurologic impairment, particularly locomotor function of the lower extremities.”

“This test is reproducible and comprehensively performed worldwide and is not affected by the difference in language and life style.”

“The number of steps was significantly lower in patients than in control and decreased with age in both groups.”

“A ten-second step test is an easily performed, quantitative task, and useful in assessing the severity of cervical spine myelopathy.”

Moreover, it can be used in determining the effects of treatment.

These authors also note that cervical myelopathy secondary to spondylosis has an insidious onset, developing over a prolonged period, and that an additional advantage to this test is to reveal the silent patient, as a screening test, who does not recognize they may be suffering from sub-clinical myelopathy. Worsening of performance on the step test indicates increasing damage to the long tracts of the spinal cord. They state:

“A test result of less than 12.8 indicates the possibility of cervical compressive myelopathy, if no other locomotor disorders are present. This value might be used as a screening test for cervical compressive myelopathy.”

Once again, it is shown that central canal stenosis of the cervical spine adversely affects the lower extremities, and such patients often have a walking intolerance. Testing lower extremity function is an assessment of the motor and sensory integrity of the outer fibers of the cervical spinal cord. The key points from this study include:

1) Myelopathy secondary to spondylosis has an insidious onset, developing over a prolonged period.

2) “Cervical compressive myelopathy is one of the most common neurologic disorders increasing in the geriatric population. It is caused by cervical spondylosis, disc herniation, and ossification of the longitudinal ligament. Symptoms include sensory disturbances of the extremities, clumsiness of hands, gait disturbance, and urinary dysfunction.”

3) “Patients with myelopathy experience difficulty in taking a step while walking, due to disorders of position sense and locomotor disability in the lower extremities, which reflect long tract pathology.”

4) The patients and controls “were instructed to take a step by lifting their thighs parallel to the floor (hip and knee joints in 90° flexion) in the same place without holding onto any object for balance. The number of steps in 10 seconds was counted. Each patient and control was requested to perform the test at maximum speed.”

5) Normal controls can perform about 20 steps in 10 seconds.

6) Proven pre-surgical patients with cervical compressive myelopathy can perform about 10 steps in 10 seconds.

7) Post-surgical patients can perform about 14 steps in 10 seconds, which is significant postoperative improvement.

8) “A test result of less than [13 steps in 10 seconds] indicates the possibility of cervical compressive myelopathy, if no other locomotor disorders are present. This value might be used as a screening test for cervical compressive myelopathy.”

9) A 10-second step test is an easily performed, quantitative task, and useful in assessing the severity of cervical spine myelopathy. Moreover, it can be used in determining the effects of treatment.

10) “The present study demonstrates that the step test can reflect and quantify the severity of cervical compressive myelopathy. This test can easily be performed anywhere and at any time without the requirement of a special instrument and repeated if necessary, as it is sensitive to neurologic impairment, particularly locomotor function of the lower extremities.”

11) Worsening of performance on the step test indicates increasing damage to the long tracts of the spinal cord.

12) “This test is reproducible and comprehensively performed worldwide and is not affected by the difference in language and life style.”

The application of these studies is to understand that patients with low back and/or leg pain may have a primary involvement of the cervical spine. All such patients should not only have an adequate evaluation of the lumbar spine, but also an evaluation of the cervical spine as well. The cervical spine evaluation should include at the minimum, imaging for cervical canal stenosis (discussed in a future Newsletter), and performance of the “ten-second step test.” If cervical spine involvement is documented, then treatment, of course, is to the cervical spine.

An often-reported protocol for the conservative management of cervical intervertebral disc herniation was written by physician Joel Saal and colleagues, and reported in the journal Spine in August of 1996. The article is titled:

Nonoperative Management of Herniated Cervical Intervertebral Disc With Radiculopathy

Spine

Volume 21(16) August 15, 1996, pp 1877-1883

The authors, Joel Saal, MD, Jeffrey Saal, MD, and Elizabeth Yurth, MD, are from SOAR, The Physiatry Group in Menlo Park, California, and Mapleton Hill Orthopaedics in Boulder, Colorado. Their paper was presented at the 9th Annual Meeting of the North American Spine Society, Minneapolis, Minnesota, October 19-22, 1994. The primary premise for this study was:

“For nonvalidated reasons, cervical disc extrusions have been frequently considered a definite indication for surgery.”

These authors note that at their clinic, “patients with cervical herniated nucleus pulposus and radiculopathy are treated with an aggressive physical rehabilitation program.” In this study, 26 consecutive patients with cervical herniated nucleus pulposus and radiculopathy were evaluated, treated, and followed-up after more than 1 year. The data analyzed included symptom level, activity and function level, medication and ongoing medical care, job status, and satisfaction. The physical rehabilitation program consisted of traction and specific physical therapeutic exercise, as follows:

“All patients were treated with ice, relative rest, a hard cervical collar worn for up to 2 weeks in a position to maximize arm pain reduction (all patients), NSAIDs for 6-12 weeks, manual and mechanical traction in physical therapy, followed by home cervical traction (all patients), and progressive strengthening exercises of the shoulder girdle and chest with training in postural control and body mechanics training.”

“A physical rehabilitation program was used for all patients, including instruction in body mechanics and adaptation of the basic and advanced activities of daily living and occupation to proper cervical spine mechanics.”

“A specific upper and lower body strength and endurance and posture program was used as well as cervicothoracic spine stabilization training.”

“The duration of this portion of the program was 3 months, at which time the patient was discharged to an independent exercise program.”

The “nonoperative treatment in the patients in the present study averaged 9 months.”

“Forceful joint manipulation was not used.”

Although the majority of patients presented with neurologic loss, the outcome results were impressive:

Twenty-four patients were successfully treated without surgery.

[24/26 = 92%]

Twenty patients achieved a good or excellent outcome, of these 19 had disc extrusions.

Two patients underwent cervical spine surgery.

Twenty-one patients returned to the same job.

These authors concluded:

“Many cervical disc herniations can be successfully managed with aggressive nonsurgical treatment (24 of 26 in the present study).

Progressive neurologic loss did not occur in any patient, and most patients were able to continue with their preinjury activities with little limitation.

High patient satisfaction with nonoperative care was achieved on outcome analysis.”

“A small percentage of patients with cervical herniated nucleus pulposus do require surgery for radiculopathy. However, the majority can be treated successfully with a carefully applied and progressive nonoperative program.”

Key points from this article include:

1) The most important point made by this article is that herniated cervical discs, even extrusion of the cervical disc, with radiculopathy (motor and sensory signs), can be successfully conservatively managed by a regime that consists primarily of exercise, traction, and mobilization.

2) The second most important point made by this article is that herniated cervical discs, even extrusion of the cervical disc, with radiculopathy (motor and sensory signs), rarely require surgery, even if they have significant extremity weakness or severe pain longer than 8 weeks.

3) The third most important point made by this article is that herniated cervical discs, even extrusion of the cervical disc, with radiculopathy (motor and sensory signs), should always be conservatively managed before surgery is warranted.

4) In this study, the success rate for conservative management of patients with herniated cervical discs, including extrusion, with radiculopathy was 24/26 = 92%.

5) Patients are unlikely to achieve good results with conservative management if the central canal stenosis is less 12 mm, or if they have clinical findings of myelopathy.

6) In this study, all patients did office and home mechanical traction.

7) The intense, in office portion of the physical rehabilitation program was 3 months.

8) The “nonoperative treatment in the patients in the present study averaged 9 months.”

9) Multilevel degenerative changes with disc herniation worsens the clinical outcome with conservative management, but these patients still did not require surgery.

10) Extruded disc material reabsorbs better than a contained disc, giving a more favorable nonoperative prognosis.

11) “The presence of radicular neurologic loss or nuclear extrusion should not be used solely as the criterion for surgical intervention.”

12) The patients did not receive “forceful joint manipulation,” but they did receive joint mobilization along with manual traction.

13) In this study, “no patients achieved an outcome in the poor category” with conservative nonsurgical management.

References

Rothman RH and Simeone FA, The Spine, second edition, WB Saunders Company, 1982.

Parke WW, “Applied Anatomy of the Spine” chapter 2 in Rothman and Simeone, The Spine, second edition, WB Saunders Company, 1982.

Bland J, Disorders of the Cervical Spine, WB Saunders Company, 1987.

Cloward RB, Cervical Diskography, Annals of Surgery, December, 1959, Vol. 150, No. 6, pp. 1052-1064.

Gorham FW, Cervical Disc Injury: Symptoms and Conservative Treatment, California Medicine, 1964, pp. 363-367.

Langfitt TW, Elliott FA. Pain in the back and legs caused by cervical spinal cord compression, Journal of the American Medical Association, May 1967, 200(5):382-5.

Lourie H, Shende MC, Stewart DH Jr, The syndrome of central cervical soft disk herniation, Journal of the American Medical Association, October 15, 1973 ;226(3):302-5.

Kabat H, Low Back and Leg Pain From Herniated Cervical Disc, Warren H Green, 1980.

Gray’s Anatomy, 39th edition, 2005, p. 318.

Kikuchi S, Watanabe E, Hasue M, Spinal intermittent claudication due to cervical and thoracic degenerative spine disease, Spine, February 1, 1996, 21(3):313-8.

Yukawa, Yasutsugu; Kato, Fumihiko; Ito, Keigo; Horie, Yumiko; Nakashima, Hiroaki; Masaaki, Machino; Ito, Zen-ya; Wakao, Norimitsu, “Ten Second Step Test" as a New Quantifiable Parameter of Cervical Myelopathy, Spine

January 1, 2009; Volume 34; Issue 1; pp 82-86.

Saal, Joel S. MD; Saal, Jeffrey A. MD; Yurth, Elizabeth F. MD; Nonoperative Management of Herniated Cervical Intervertebral Disc With Radiculopathy, Spine, Volume 21(16) August 15, 1996, pp 1877-1883.